With all due respect, I would like to respond to Brehan Furfey’s (furbearer project leader for the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department) characterization of regulated trapping in Vermont as a necessary wildlife management tool. (see article below) I am a lifelong wildlife advocate and since 2014, I’ve investigated human conflicts with wolves in Wisconsin. For the last four years I have lived in Vermont where I am the caretaker for a large botanical sanctuary and 250 acre private wetland in Central Vermont.

Last October, I discovered a trapper hired by VTrans placing body-gripping and foothold traps on the wetlands that I manage. I had recently legally posted the property closed to hunting and trapping at the landowner’s request. VTrans and my local warden cited a legal right of way that allowed trapping up to 200 feet inside of an otherwise protected wetland. All the beaver in our protected wetlands have been trapped out by the state’s contracted trappers.

When I requested records from VTrans related to their statewide nuisance trapping program, I learned that the agency contracts with trappers like the one I found placing traps, who also was cited by wardens in 2022 for illegally taking a fisher out of season. The animal was found alive on a snowmobile trail with a body-gripping trap on its head that had crushed its jaw. In May 2022, the same trapper caught an otter out of season in a body-gripping trap while targeting beaver for VTrans in northern Vermont. In September, they caught another otter accidentally before coming to our wetlands and killing one beaver kit. Who knows just how many non-target animals this trapper actually caught, since all the data is based on self reporting?

Vermont Fish & Wildlife is currently adopting new trapping rules that it argues improve animal welfare and I’ve attended Fish & Wildlife Board meetings where VFW Commissioner Christopher Herrick has called any and all critics of VFW’s proposed trapping rule changes uneducated. The Department’s broad support for trapping has made the furbearer department a public relations extension for trapping and the commercial fur trade. Due to global opposition to the cruelty inherent with trapping, since the 1990’s the fur trade has been fighting for its own economic survival with efforts to convince the public that trapping is humane and actually helps the wildlife it kills, which of course can then be sold on the international fur market.

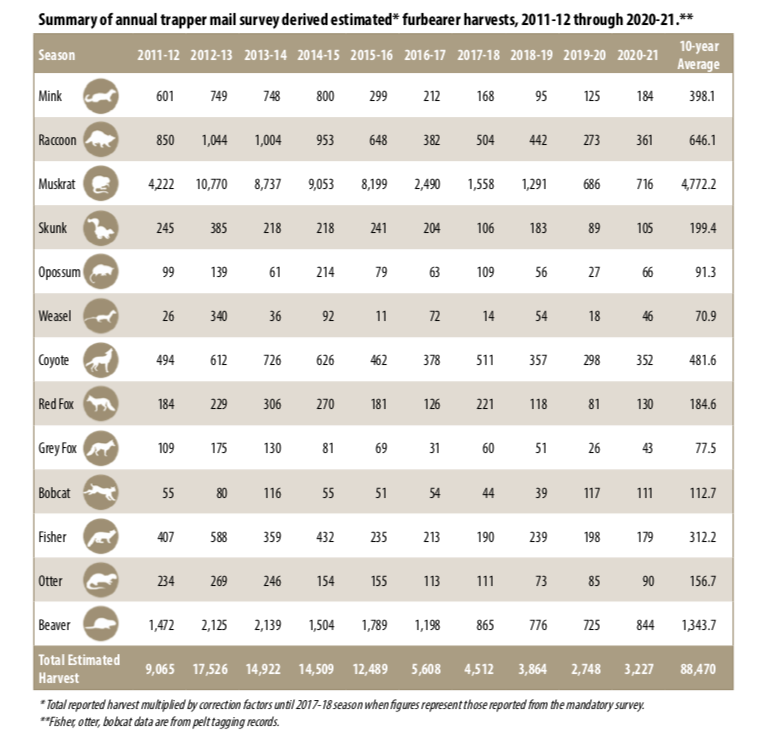

“Regulated” trapping is the only practice in Vermont where it is legal to kill public trust wildlife and sell it. Regulated trappers are allowed to trap all year “in defense of property” and in the regular October-March trapping season there are no limits on the number of traps a trapper can use or limits on the number of beaver, otter, fisher, mink, bobcat, coyote, raccoon, fox, weasel,muskrat or skunk a trapper can kill. Hardly regulated.

Since 2018, it has been mandatory for Vermont’s licensed trappers to report their kill and provide carcasses of some animals. Furhey says the state owes much of its furbearer conservation success to this data collected from the regulated trapping season saying, “there is no alternative way to gather these valuable samples for research and monitoring.”

While VFW’s furbearer department argues that trapper harvest data is the most important source of information available for wildlife monitoring, at the March 15, 2023 Vermont Fish & Wildlife Board meeting which I attended, VFW furbearer biologist, Katherina Gieder cited other data sources such as remote cameras, deer hunter sightings, public reports, roadkill and research studies. “Because you really do have to try to rely on a broad range of information for managing such a broad species.” In Wisconsin and other states, nonlethal hair traps also provide valuable DNA on furbearers like marten.

Another fault with trappers as the state’s biological data collectors is the fact that according to records recently provided by VFW, up to 30% of Vermont’s licensed trappers are out of compliance for failing to return trapper surveys. For the 2020-21 regulated trapping season for example, only 72% of the state’s regular licensed trappers returned their mandatory surveys.

Furhey also claims that regulated trapping was banned in Massachusetts in 1996 leading to a beaver population explosion. Yet, it wasn’t all regulated trapping that was banned in Massachusetts, only the use of foothold, body-gripping traps and snares. After adjusting to the change, the state’s Division of Fisheries & Wildlife has established a better nuisance trapping licensing system and now uses more nonlethal measures to address beaver and other wildlife conflicts.

Furhey also cites increased costs to towns and highway departments (like VTrans) in Massachusettes due to the limited trapping ban, arguing that employing lethal trapping saves money. Yet, according to records recently obtained from VTrans, the agency spends far more on trapping than the figures cited by Furhey. In January 2023 alone, VTrans paid one trapper $2,236.99 to trap four beavers on the D&H Rail Trail in West Pawlet, Vermont. The agency also paid $3,848 during the same month to remove beaver debris. Those costs alone could have coveredthe costs of a long-term non-lethal solution such as the installation of a beaver deception device.

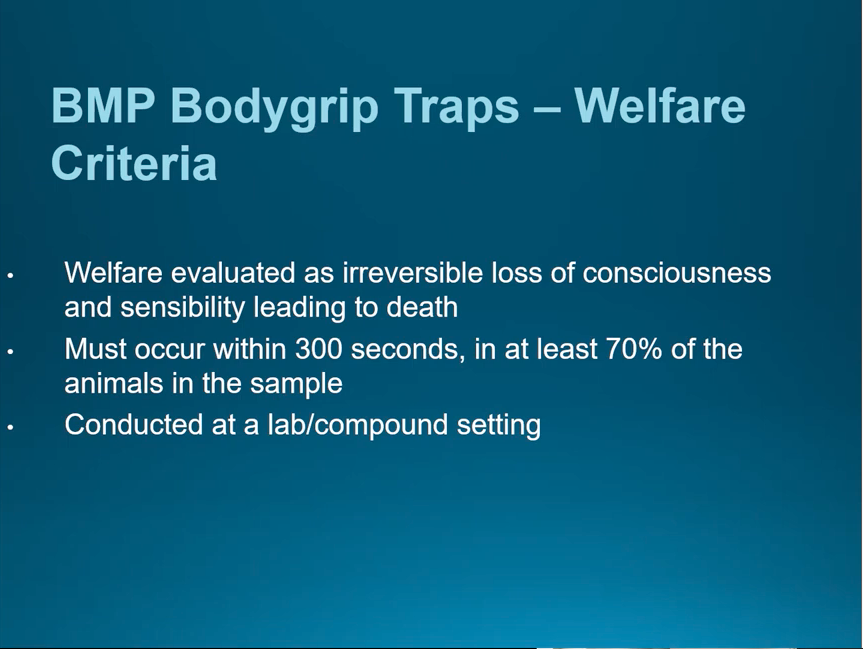

Furhey also states that VFW, “drew from peer-reviewed research to identify ways to make trapping safer and more humane.” But when you review the department’s recommended trapping changes, there are no restrictions on the use of Conibear body-gripping traps that research has determined are ineffective at killing fishers within the required 5 minutes to classify as a “Best Management Practices” approved trap.

In addition, research findings published by the Association Of Fish & Wildlife Agencies and included in the minutes of the April 5, 2023 Fish & Wildlife Board meeting detail body-gripping traps sometimes taking up to nine minutes to kill beaver in laboratory tests where anesthetized animals are placed in traps. These are the kinds of experiments Vermont Fish & Wildlife claim are necessary in order to make regulated trapping more humane.

Lastly, Furhey says new trapping rules will, “create a 25 ft – 50 ft. safety buffer between public roads, trails on most state lands, and the places where most traps can be set.” In reality, this rule will not apply to national forest lands, Vermont’s 100 Wildlife Management Areas and privately owned trail systems nor does it cover the use of underwater body-gripping traps and foothold traps used as drowning sets which can still be placed only feet off of trails as they are used along the D&H Rail Trail in West Pawlet and on my own property by VTrans.

To add insult to injury, Vermont’s trappers are asking the public to cover the costs of purchasing “new and improved” BMP traps including body-gripping traps that take minutes to kill their victims. In their report to the Legislature VFW says those costs will be $300-$400,000.

Vermont Fish & Wildlife’s endorsement of trapping serves the interests of less than .05% of the state’s population while ignoring the over 68% percent of residents opposed to recreational trapping according to VFW’s own surveys. The public was told by VFW that those surveys would guide the future direction of the furbearer program.

Instead Vermonters should look at the recent appointment of two trappers to the state’s Fish & Wildlife Board by Governor Phil Scott, as an indicator of the true direction of our public wildlife agency whose mission it is to protect wildlife for ALL the people of Vermont, not only those profiting from its death.

Wildlife Conservation Depends on Regulated Trapping

Brehan Furfey is a wildlife biologist and the furbearer project leader for the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department.

Wildlife conservation is complicated. In Vermont, that complexity is front and center in recent conversations around regulated trapping. Although this topic deserves Vermonters’ careful consideration, I worry that some are losing sight of the conservation benefits that regulated trapping provides.

I am Vermont’s new state furbearer biologist. I earned my master’s degree in biology at Arkansas State University, and I have worked on complex conservation issues across the country, most recently with wolves in Oregon. In each case I have seen knee-jerk reactions overshadow the nuances of effective conservation, often to the detriment of wildlife. I see the same trend playing out, again, as Vermonters argue about trapping without seeing the full picture.

I want to be clear: even if it seems counterintuitive, regulated trapping is a critical wildlife management tool that benefits furbearer populations.

Vermont is at the cutting edge of furbearer conservation. Species like bobcat, mink, and Eastern coyote thrive on this landscape, and populations of every species that is trapped in our state are healthy and abundant. Vermont owes much of that conservation success to data collected during our regulated trapping seasons.

Despite the clear intent of the NAMWC being the elimination of the commercial sale of wildlife, agencies like Vermont Fish & Wildlife insist the sale of fur from trapped animals is highly regulated.

Vermont’s trappers are part of a community science system. Samples from our regulated trapping seasons contribute to one of the country’s longest running datasets on furbearers, helping state biologists identify potential threats to both wildlife and humans. We analyze tissue from fishers and bobcats for potential exposure to rodenticides. We track rabies distribution to measure spread on the landscape and evaluate the success of ongoing control efforts with our partners at the U.S. Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services. And our collaborators at the University of Vermont use genetic samples from fisher, bobcat, coyote, and fox to map furbearer movements across the landscape and to look at the spread of Covid (CoV2) in wildlife populations.

As we consider the role of regulated trapping in Vermont, it is important to understand that there is no alternative way to gather these valuable samples for research and monitoring.

Wildlife cameras cannot collect tissue. And furbearers trapped by professionals for damage or nuisance reasons would not provide a comparably large or diverse sample to that generated during our regulated trapping seasons. Without regulated trapping, state biologists and our conservation partners would lose our ability to gather sex, age, and distribution data that are essential for monitoring species like bobcats and otters. We would also lose the ability to detect and respond to emerging wildlife diseases, environmental toxins, and habitat loss.

Regulated trapping provides social benefits, too. Many of Vermont’s wildlife conflicts are addressed during our regulated trapping seasons. The animals taken are utilized for food and fur. The costs, labor, and rewards of coexisting on a landscape with furbearers are shared by our neighbors.

So, what could it look like for Vermont communities if regulated trapping was outlawed, and nuisance control trapping was outsourced to businesses?

When regulated trapping was banned in Massachusetts in 1996, the beaver population doubled. Public support for beaver and the valuable wetlands they create declined. The cost for dealing with human/beaver conflicts increased dramatically. Towns and highway departments faced bills from $4,000 to $21,000 per year from 1998-2002 to deal with human/beaver conflicts. Individual landowners paid upwards of $300 per beaver to have them trapped by nuisance animal control contractors. In many cases animals trapped as nuisances were not used for fur or food.

Of course, Vermonters need to weigh the scientific and social benefits of regulated trapping against understandable concerns about the safety of pets and the suffering of trapped animals.

Recognizing this, the Fish and Wildlife Department is developing new trapping regulations at the direction of the legislature. In 2022, we worked with a diverse group of stakeholders and drew from peer-reviewed research to identify ways to make trapping safer and more humane. This spring, we will invite public comment on proposed regulations to: limit legal trap types in Vermont to the most humane standards based on peer-reviewed research; protect birds of prey and pets from being attracted to baited traps; and create a 25 ft – 50 ft. safety buffer between public roads, trails on most state lands, and the places where most traps can be set. Once finalized, these regulations should go into effect in 2024.

We believe that stronger regulations to reduce risks are in line with public opinion. 60 percent of Vermonters supported regulated trapping in a statistically representative state-wide survey last fall. And although Vermonter’s opinions vary regarding different reasons people may trap, 60 percent also supported the right of others to trap regardless of their personal approval of trapping.

As Vermonters consider regulated trapping’s role on our landscape, it is crucial to understand the complexity of the conservation challenges at hand—and the practical solutions the Fish and Wildlife Department is working towards.

May and June 2023 – Vermont Fish & Wildlife will accept public comment on new proposed regulations on trapping and will make additional recommendations to the proposal advanced by the board on April 5, 2023. Read the BMP Legislative Report with Responsiveness Summary and Attachments

Public comment emails on trapping in Vermont can be sent to ANR.FWPublicComment@vermont.gov Deadline for comments is Friday, June 30, 2023.

Public hearings will be held in person and online at:

- Tuesday, June 20, 6:30-8:30 pm. Rutland Middle School, 67 Library Avenue, Rutland VT | map

- Wednesday, June 21, 6:30-8:30 pm. Montpelier High School, 5 High School Drive, Montpelier VT | map

- Thursday, June 22, 6:30-8:30. Online via Microsoft Teams at: https://tinyurl.com/trappinghearing

Good analysis.

Yes, trapper harvest data only provide one, unfortunately subjective, source of information about wildlife populations. As you point out, other and better sources of information include “hair traps,” “remote cameras, deer hunter sightings, public reports, roadkill, and research studies.”

Yes, Flow Devices can provide more environmentally-sound and economically efficient solutions to problems with beaver dams: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_device#

Yes, “non-target catch,” including the deaths of our family dogs in body-gripping traps, is a major problem that the trapping lobby refuses to recognize or address: https://www.doglovers4safetrappingmn.org

Thou Shalt Not Kill applies to ALL sentient life forms and to Mother Earth herself & is not limited as merely “Thou Shalt Not Kill Humans”. ALL IN CREATION HAS THE SAME RIGHT TO BE FREE and EXIST IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE NATURAL LAWS THAT CREATED US ALL. Never Trap, harm, kill. Indigenous Beings must make their come back NOW. No ,=more favors to Catle ranchers, dairy farmers etc… no more destruction, water waste, toxins that kill.