I moved to Vermont in 2019 and live on land that is home to moose, bear, coyote, bobcat and until recently, beaver. I am a caretaker of these wild and wetlands. I am also a descendent from the Yoeme Nation, (more commonly known as Yaqui Tribe). I would like to speak to the heated debate about trapping in Vermont, and the history of the fur trade in New England. Last October, when a trapper hired by the Agency of Transportation (VTrans) came onto our lands and killed every beaver in the colony we share our land with, I learned that in Vermont it is legal to use body-gripping and foothold traps to drown beaver, otter, mink, muskrat in all waterways including our protected lands. I also discovered that the trapper hired by VTrans was cited in 2022 for taking a fisher out of season when the injured animal was discovered on a snowmobile trail with a body-gripping trap crushing its mouth and head.

Like a lot of indigenous people, I did not grow up in my own culture, with my own language or in my homelands, but I was still always taught to respect nature and animals. I have lived on our reservation in Arizona, learned from my elders, participated in ceremonies and been blessed to know many of this country’s traditional indigenous elders. The first time I participated in a traditional ceremony, I heard Lakota elders praying to animals and plants as well as to our human ancestors. In the years since, I have been fortunate to experience indigenous ceremonies that were once illegal in this country because they represented a worldview that saw animals as our sacred relations.

What my culture has taught me is despite centuries of persecution, indigenous people today remain a proud distinct people with a worldview that places animals, plants, rivers, forests and people in the same circle. We are all related. My elder, Anselmo Valencia Tori, spoke to animals and spirits. He used to say that when he was my age, their voices were much louder. Albert White Hat was a Sicangu Lakota elder I knew who spoke of the time when animals and humans were more closely related. His ancestors fought a war to save the buffalo. He used to say when humans are ready to live in harmony again with all life around us, animals that we thought were gone forever, like the wolf, will begin to return. I am one of the many people who are ready to live in such peaceful coexistence with the natural world of these once and still sacred lands.

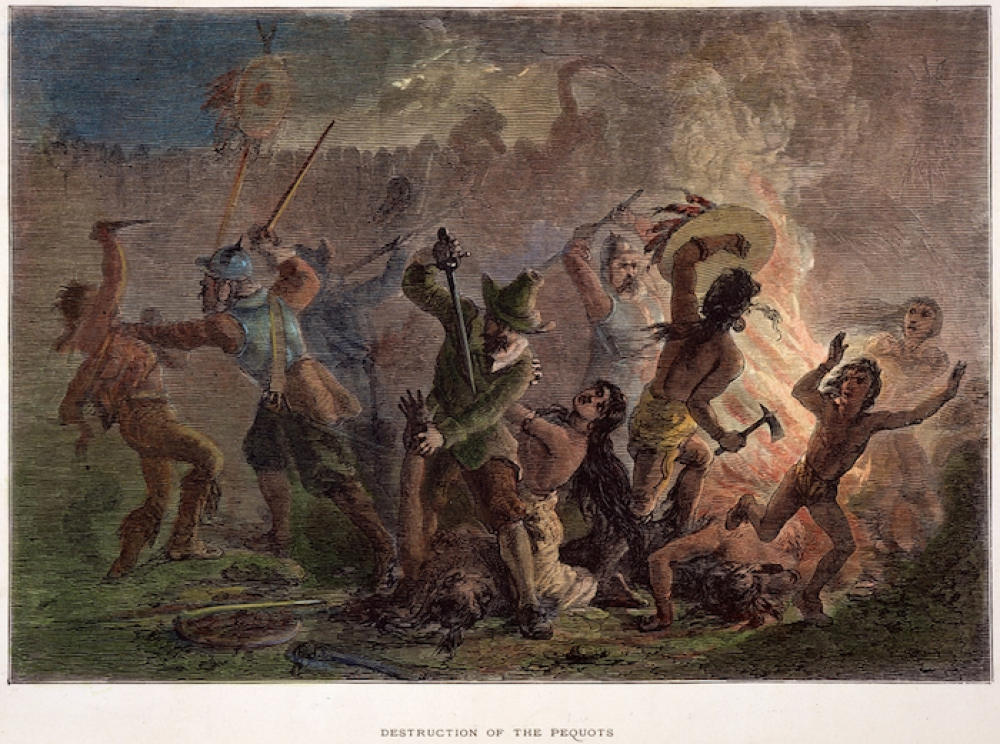

A bit of history. By the early 17th Century, Europeans had decimated their native furbearer populations and needed a new source for their exploding fur market. The fur trade turned to North America and thus began centuries of violence against the indigenous inhabitants and native furbearer populations. Entire indigenous nations were wiped out or forced to assimilate into other tribes and colonial life, all because of the economic demands of the fur trade. In 1620 Samuel de Champlain listed, “bufles (buffalo) moose and elk” as important resources in New France. By the time of the first European settlement in Vermont in the mid-18th Century, many species were already near extinct because of the fur trade. Other non-furbearer native species to Vermont like Bison, Caribou and elk would soon be wiped out in the early colonial period. Beavers would be gone by the 1850’s.

The first wave of European fur traders in North America also brought diseases that literally wiped out entire villages in what is today New England. A Smallpox epidemic introduced by a Dutch fur trader in 1633 left a community of 1,000 with only 50 survivors. Before the epidemic ended, a number of tribes had lost their individual identities in the land we now call Massachusetts. Remnant indigenous survivors were quick to join the fur trade, not because they wanted to, but because it was the only way to survive. Without the stability of pre-contact communal life, many indigenous people became trappers to obtain the guns, powder and metal tools they needed for survival and subsequent warfare as tribes fought for the control of lands to exploit for fur.

For almost the entire 17th Century, the French, English, Dutch colonists and indigenous nations fought violently for control of the new fur trade from New England to the Ohio Valley. It was even called the Beaver Wars, though most of us know it as “The French & Indian War.” I am opposed to the commercial fur trade, not because I am an animal rights activist, but because as an indigenous person today, the fur trade and trapping still represents a historic institution of colonization and assimilation that continues today with our government’s support. That kind of support is clear and abundant when Vermont Fish & Wildlife (VFW) defends its partnership with trappers today while at the same time distancing itself from the bloody history of the commercial fur trade in North America.

In January 2023, Paul Noel, a vocal trapper and member of the Vermont Trappers Association wrote a commentary describing trapping as, “The ecological understanding and reverence that we feel is enhanced by direct experience with the natural world, and lessened by the lack thereof. Trapping, hunting and other consumptive activities provide a historical conduit to that world. That ancient, indigenous wisdom should remain intact.” Noel was appointed to the Fish & Wildlife Board in March 2023. Another trapper, Marty Van Buren was recently re-appointed to a six year term on the Fish & Wildlife Board as the agency begins the rule making process for Vermont’s new trapping rules. The true indigenous wisdom of the Abenaki people is being ignored by institutions like the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department, in favor of the colonial worldview that now posits that trappers are “citizen scientists” who love wildlife more than anyone only wildlife advocates are too uneducated to understand.

Promoting trapping as a way to live harmoniously with nature becomes a false narrative when it implies itself to be part of indigenous wisdom. The Oxford Dictionary defines the word indigenous as; “originating or occurring naturally in a particular place; native.” and “(of people) inhabiting or existing in a land from the earliest times or from before the arrival of colonists.” While North American indigenous peoples have always used hides and fur for clothing and shelter, the way we lived with wildlife before the introduction by early Europeans of disease and the commodification of our animal relations compares not at all to the commercial exploitation of furbearer species on this continent by trappers and the fur trade. Early indigenous communities in present-day New England practiced conservation using closed seasons on hunting, cultivation of grasses and controlled burning to improve habitat for elk, deer and other animals. What European trappers did to New England and the entirety of North America by eradicating literally hundreds of millions of wetland creating beavers was an ecological catastrophe.

In a February 2023 commentary, Mike Covey of the trapping lobbyist group, Vermont Traditions Coalition, which proclaims to be, “Representing Vermont’s Original Conservationists and Environmentalists” wrote, “In a time where we are striving to reach a standard of inclusivity, the only thing we should be legislating against in Vermont is hypocrisy and hate, not a healthy self-sufficiency in harmony with the renewable life cycle of nature.” Covey present’s Vermont’s 300 licensed active trappers as an oppressed minority and equivocal to victims of hate. The minority defense is part of the narrative promoted by the Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies (AFWA) and Vermont Fish & Wildlife. AFWA staff regularly work with member agencies, including the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Furbearer Management Team, and have developed a strategic plan for effective communication about regulated trapping and furbearer management. Here is a passage from AFWA’s “Regulated Trapping and the North American Conservation Model”:

“In the United States, Jeffersonian democracy protects the rights of minorities against the tyranny of the majority who may wish to impose their will and standards. Within the public, furbearer trappers, and hunters, are a minority group…their opportunities to access wildlife that is allocated by law should be protected if we are truly a free people.”

When I hear trappers claiming to be an oppressed people, I hear the continuing perpetuation of a historical hypocrisy and hate by the same colonial forces responsible for destroying our way of life they now claim was their own. Trappers in the bygone era did not live in harmony with nature, they were responsible for the extinction of both humans and animals. The minority experience in America is a long history of violence directed against other Americans based on their race, religion or beliefs. Global opposition to the inherent cruelty associated with trapping and the fur trade has led to its steady decline. Simply because a few hundred people in Vermont cling to this practice does not make them minorities or oppressed. Another misrepresentation promoted by VFW is that “regulated” trapping is not responsible for the wrongs of the fur trade in past centuries yet, Vermont’s trappers still claim trapping as a centuries old tradition.

Lastly, I want to draw attention to the current legal methods for trapping fisher and beaver in Vermont. I am citing a published research paper on tests conducted on live fishers at the Fur Institute of Canada’s research facility in Alberta in 1997. Best Management Practices (BMPs) for trapping were first created by the international fur industry itself, in response to the 1991 European Union’s ban on the importation of fur from animals caught with inhumane traps. Since then, there have been ongoing experiments in Canada supported by AFWA & VFW where anesthetized animals are placed in body-gripping kill traps to test if they are killed within 5 minutes in 70% of the tests, as required to meet trapping BMP standards.

Canadian researchers concluded that some body-grip traps currently in use in Vermont, “failed to render irreversibly unconscious in 3 min. Fishers single-struck in the head-neck region, or double struck in the neck and thorax regions. Although the Conibear 220 trap is often recommended as an alternative to the steel leghold trap, it is unlikely that it has the potential to humanely kill fisher.” Yet this trap will still be legal to trap fisher in Vermont under the new Best Management Practices. Included in VFW’s January 2023 report to the Vermont Legislature is a request to allocate $300-400,000 to reimburse the costs to Vermont’s trappers for new BMP traps that will still kill inhumanely.

Trap research experiments conducted, not to save lives, but in order to refine killing methods to produce a fur garment, are not what I want one cent of my taxes to pay for. The live fishers used in these experiments are fully conscious when they are placed in these traps, they have only been immobilized with Ketamine which is a paralytic not anesthesia. Like a lot of people fortunate enough to live in the forests of Vermont, I have grown a special kinship to my nonhuman neighbors. I’ve seen moose, bear and fisher all raising their young on this land that owns me. I have also met trappers who are good people and believe some to be true naturalists and ecologists, but as in any practice, there are those who don’t follow the rules, like the 30% of licensed Vermont trappers who fail to return mandatory kill surveys according to VFW records.

So when I hear Vermont’s trappers talk about their traditions and not wanting to change, I remember the trauma indigenous peoples have suffered for centuries for simply wanting to survive and honor their own traditions. I think of the herds of bison, elk and caribou that once existed and that I’ll never see because of the rapacious behavior of the fur trade and early colonists. In order to co-exist with our ever-growing neighbors, we must all be willing to change and evolve towards a more peaceful way of living with everyone around us. After four centuries, the fur trade continues to violently impact my life and the lives of our animal relations in “New England.” Vermont’s furbearer are more important than the data collected from their carcasses and the money still paid for their pelts on the open fur market. It’s time to put trapping in the history books and move towards more nonlethal and peaceful solutions to conflicts with the wildlife and people around us.